Walter Zumbrunnen was the first man to adopt the Zumbrunnen surname. So his eldest son Burkhard Zumbrunnen must have been the second man in history with this name.

Burkhard would have been born in the late 1100s or early 1200s. He was the grandson of Werner, the Baron of Attinghausen, but Burkhard was not nobility himself. While many junior branches of Medieval nobles disappeared into obscurity, this was not to be the case with Burkhard. We know Burkhard through two interesting records that show he was an early participant in institutions that became Democracy, and was a key figure in the establishment of Switzerland as a nation.

The first known leader of the people of Uri (the mountain valley from which the Zumbrunnen originate) was Burkhard’s grandfather: Werner of Attinghausen. Werner was a baron of the Holy Roman Empire, but according to the ancient historians of Uri, as early as 1206 he also held the unique Swiss title of Landammann.

Landammann translates to something like the leader of the land, or the magistrate of the land. Even very early on, the person was elected by the other members of his community.[1] But whereas a Baron received his authority from the Emperor, very early on the title of Landammann implied someone who was a leader of the people of the land. Historians today recognize these Swiss Landammanns as one of the very earliest examples of Democratic leaders emerging from the Middle Ages.

Werner’s son (also named Werner) became the second landammann of Uri by 1234. By 1241 he was succeeded by Burkhard Zumbrunnen, the third landammann of Uri.

I doubt any records will ever be uncovered of how exactly Burkhard assumed his office, but the mere fact that he assumed the office as a non-noble is remarkable. Nearly all leaders in Europe of this time held noble titles or were religious figures yet Burkhard was neither.[2]

Whether he knew it or not, Burkhard was an early participant in a bold experiment in human society. In the mid-1200s, while most of Europe were engaged in bloody struggles among nobles for power over their minions, the people of central Switzerland were carving out a different model, one in which people were free, selected their own leaders, governed their own lives, and protected each other from violent incursions. We know nothing of Burkhard’s personal views, but a document survives showing something of his actions.

History buffs may know that the founding of Switzerland is often dated to 1291, when three of the Alpine mountain valleys, Uri, Schwyz and Unterwalden, concluded an eternal alliance of protection. (Or to 1307 when the story of William Tell took place.)

But even before then, the people of central Switzerland had begun to form alliances with each other. Burkhard participated in one of the earliest known alliances. In 1251, toward the end of his term as landammann, the cantons of Uri and Schwyz and the city of Zurich swore an alliance, agreeing to protect each other from foreign incursions. I presume the original is long lost, but in the 1500s, scholars began including transcriptions of such ancient documents in their history books. A scholar named Josias Simmler transcribed an old German document in the archives of Zurich, dating back to the year MCCLI, or 1251.[3]

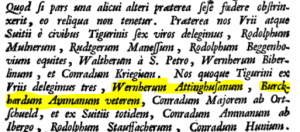

Werner of Attinghausen and Burckhard, listed as delegates to a 1251 alliance between the Canton of Uri and the city of Zurich

I located a copy, and although I can’t read Latin, found the passage where the delegates of Uri are named. They were the men who swore the alliance, and would have been listed from the very beginning as the witnesses to it. In highlights you can make out the name of Wernher of Attinghausen (the first Werner must have died by now, so this was likely Burkhard’s uncle or cousin) and Burkhard. He is identified in this Latin translation as “Burckhardum ammanum veterem” or “Burkhard, the old landammann.”

This is stuff from the mists of time, and little is known about it. But this alliance that Burkhard swore would be periodically renewed. The bond between Zurich and Uri has never been broken. The alliance between the central regions of Switzerland would grow stronger and stronger, and its society would become more and more democratic. We don’t know much about this era, from which Swiss Democracy emerged, but we know our ancestor Burkhard Zumbrunnen participated at the very beginning of it.

Questions for Further Research

1) It’s not known for certain how the very earliest landammann were picked, but the consensus among historians is that it became a recognizably-democratic process as early as the 1200s or 1300s.

2) The fact that his grandfather and uncle were barons probably helped it seem palatable that Burkhard could serve as leader, but none of the old sources I’ve found suggest that Burkhard used any sort of noble titles.

3) A discussion of Simmler’s transcription is available on page 40 and 41 of a book on Swiss historical practices, titled “Storing, Archiving, Organizing: The Changing Dynamics of Scholarly Information Management in Post-Reformation Zurich.”

[…] in historical records alongside Burkhard Zumbrunnen. In 1251, the elder Werner and Burkhard helped forge an alliance with the city of […]