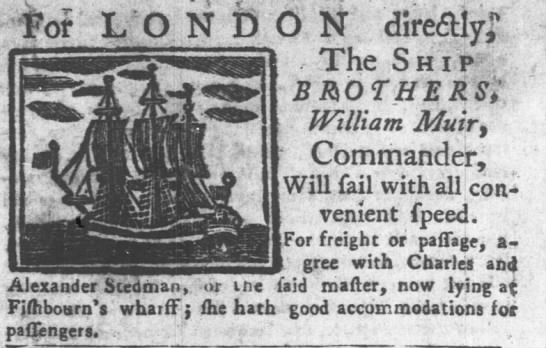

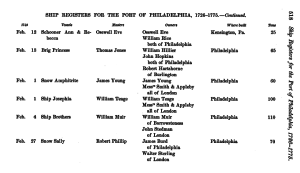

In the summer of 1754, our ancestor Heinrich Zumbrun and about 250 other passengers boarded the ship “Brothers” in Rotterdam in South Holland, under the command of a Scotsman named William Muir. This is the story of what we know about Heinrich’s voyage to became the first Zumbrun in America.

The “German” Immigrant Wave

The American colonies in the 1700s were eager to grow their populations to harvest a nearly endless supply of fertile soil. The population of Philadelphia was only about 15,000 to 25,000 in the 1700s, far too few people to take full advantage of the abundance of the New World. A massive immigration of German-speakers of the Rhine Valley (also known as Palatines) to Pennsylvania began in the early 1700s. By the 1750s when Heinrich boarded his ship, over 5,000 German speakers were arriving to Philadelphia each year.

We don’t know Heinrich’s reasons for leaving Europe. In the early 1700s, the first German-speaking immigrants often traveled in large groups of extended families that belonged to the same persecuted religion. But by the 1750s when Heinrich Zumbrun traveled, the immigrants were more likely to be individual families traveling for other reasons. Immigration slowed when periods of war disrupted Europe: 1733′s War of Polish Succession, the War of Austrian Succession in the mid-1740s, the Seven Year’s War beginning in Europe in 1756 (Heinrich got out just in time). Many of the immigrants traveling shortly after these slowdowns were essentially war refugees.

A note on “German”: these immigrants spoke German but the modern country of Germany did not exist at the time. The English called all the immigrants Palatines, though many were not actually from the modern German Palatinate. The regions that today are part of Germany were, in the 1700s, a fragmented patchwork of tiny little territories governed by different counts or princes or bishops, who owed allegiance to the Holy Roman Empire. Many of the “Palatines” were in fact German-speaking Swiss, distinctions that meant little to the English-speakers who ran the colonies.

The early German and Swiss immigrants genuinely thrived in the United States, so word traveled across the German-speaking world about this land of opportunity and religious freedom. Because there were profits to be made, Pennsylvania distributed promotional literature about its colony, and the shipping companies sent recruiters out from Rotterdam to persuade immigrants to make the journey. Recruiters traveled down the Rhine River (the most convenient way to venture deep into continental Europe) and make presentations about the colonies. Many Palatines needed little convincing.

The Journey

Immigrants like Heinrich would leave in the spring or early summer to travel up the Rhine River to Rotterdam. They would stay in Rotterdam a few weeks or months before setting sail. Heinrich’s ship departed Rotterdam on July 31, 1754, and sailed to Cowes, on the Isle of Wight. The ships typically took about a week to reach Cowes and then were there another week to clear the customs house (this was when the ships officially entered the English Empire) and stock up for the journey. Heinrich’s ship likely left Cowes around mid-August.

The journey to the New World typically lasted 6 to 12 weeks, depending on the weather and the conditions of the ocean. You can read a particularly harrowing account of the passage written by a contemporary of Heinrich’s named Gottlieb Mittelberger.

Heinrich’s passage was likely easier, however, as historians now believe Mittelberger both traveled under especially poor conditions on an overcrowded ship, and still exaggerated how bad it was. That said, about 3.8% of German immigrants in this era are estimated to have died on the voyage.

Heinrich’s ship arrived in Philadelphia with 250 passengers on board, so if his journey was average they would have set sail with about 260 passengers, 10 of whom died along the way. The journey was especially hard on children, about 9% of whom died. (While better than Mittelberger’s claim that children “rarely survive,” it would still have been a traumatic journey.)

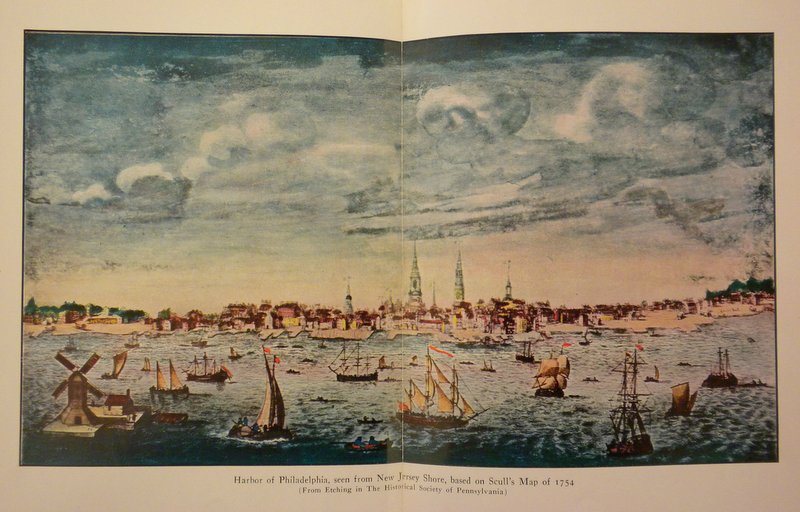

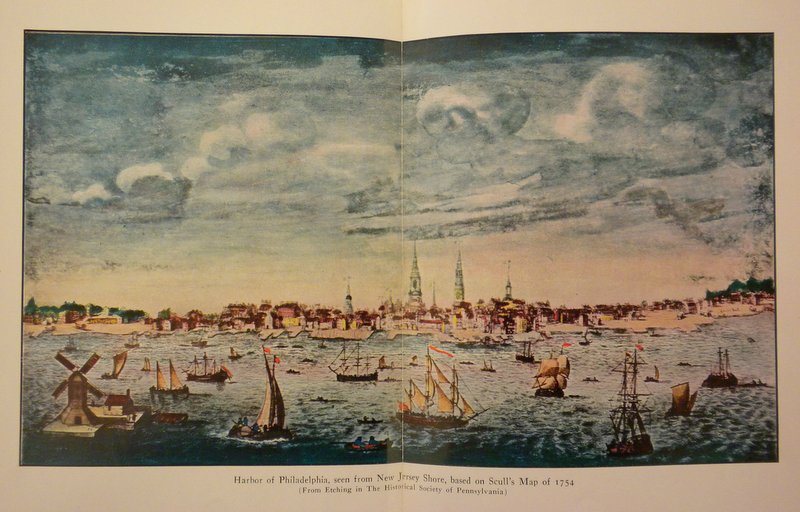

Assuming a departure from Cowes of August 15, Heinrich’s ship “Brothers” appears to have sailed the Atlantic in under 7 weeks. On September 30, 1754, Heinrich’s ship disembarked in the Harbor of Philadelphia and his life in the new world began.

“Harbor of Philadelphia, seen from New Jersey Shore, based on Scull’s Map of 1754″ (From etching in the Historical Society of Pennsylvania)

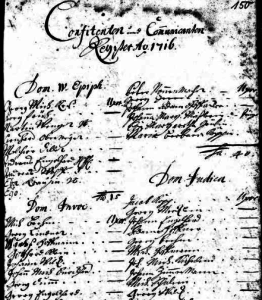

The Ship Records

We know Heinrich was on this particular ship because, in 1727, as German-speakers poured into Pennsylvania, the English became wary of the flood of immigrants (a recurring theme in American history), and required captains and the ports to start keeping arrival records. Before getting off the boat, the immigrants underwent a “health certification” to make sure they didn’t have infectious diseases. The certification for Heinrich’s ship reads:

Sept 30, 1754 Sir, We have carefully examined the State of Health of the Mariners and Passengers on board the ships Brothers and Edinburgh, Capts. Muir & Russel, and found no objection to their being admitted to land in the City immediately. To His Honour The Governour Tho. Graeme Th. Bond

Heinrich was healthy enough to leave the ship, and is thus recorded that same day on a handful of lists. (The sick passengers remained on the ship or went to a “hospital” on a nearby island in the Delaware River until well enough to enter Philadelphia.) According to Marianne Wokeck, a historian whose work I drew upon heavily in this blog post, these lists had two motivations:

The first was to appease the Englishmen’s traditional xenophobia to keep track of “different” peoples coming to live alongside them. The second was to establish a genuinely constructive, regulated first step towards eventual full citizenship for non-British immigrants by permitting settlers from places not under British rule to acquire, hold, and sell property.

The captain was required to keep a list that included all his passengers, their occupations, and their former place of residence. Sadly, most captains only followed part of this instruction. Muir only followed the instructions to record the names of adult men (though he also submitted their ages, which he wasn’t required to do; Heinrich gave his age as 36, making him born in 1717 or 1718).

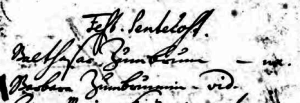

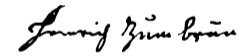

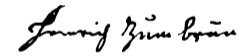

Heinrich’s signature of abjuration from the pope.

Then, the immigrants walked in a line to the Philadelphia State House to sign oaths, of allegiance to the British crown and of abjuration against the pope. Thus we have a copy of Heinrich’s signature written in his own hand, so know he was literate (and that he had better penmanship than most on his ship).

For more information on the ship records, see this related post:

Original Sources: The Passenger List and Registry for the Ship “Brothers”

The Price of Passage

Passage cost between 6 to 10 pounds sterling for adults, while fares for children were half price from ages 5 to 10, and free for those under 5. I’ll present evidence in a future post that Heinrich traveled with at least a wife and possibly two children, meaning that his fare would have been somewhere between 10 and 30 pounds sterling.

This was merely the cost of passage from Rotterdam to Philadelphia. Traveling from his home to Rotterdam, lodging and food in Rotterdam (an expensive city at the time) while waiting to sail, and fees in Philadelphia may have tripled the cost according to some estimates. In total, Heinrich’s journey must have cost between 30 to 90 pounds sterling.

It’s hard to convert currencies across centuries. A converter at this website suggest such a sum today would be around $7,000 to $20,000. Perhaps a better way to think about it is to consider that 1 pound sterling was around 450 grams of silver. A German laborer in the 1750s earned an average of just over 4 grams of silver a day according to data from the Global Price and Income History Group. Thus it would take nearly 100 days of labor to amass just one pound Sterling. It was a considerable sum.

There were three ways passengers made this trip:

- Those who could afford the trip were welcome to pay up front, and received a discount for doing so. (More precisely, passengers who did not pay up front were assessed additional fees in Philadelphia.)

- “Free-willers” were those of modest means who arranged with a ship captain or shipping company to repay the trip upon arriving in Philadelphia. Sometimes family members or a religious community could muster the necessary funds; other times they went into debt to the shipping company or its captain.

- “Indentured servants” were the poorest immigrants who went into debt before leaving home and often had the most onerous contracts to get out of.

I’ve found no record of Heinrich being any sort of indentured servant, so he may have somehow had the means to pay for the trip. Such records can be hard to find, and Heinrich may have begun toiling to repay his debts the day he arrived.

His motivations and means of funding the journey may be lost to time. But we know for certain that on September 30, 1754, Heinrich Zumbrun set foot on American soil after a long and arduous journey, and that because of him, the Zumbruns have been here ever since.

Some questions for further research

- Are there records of Heinrich being an indentured servant or in debt from the voyage? The captain (William Muir) or shipping company (Stedman Brothers) may have had them.

- Were any relatives, friends or associates of Heinrich among the other passengers?

- Are there any records of Heinrich in Rotterdam?

- What happened to the ship “Brothers”? What did it look like?

Sources