In researching the Zumbrun family, one name jumps out with particular frequency: Heinrich and its English equivalent Henry. There’s a fascinating story behind the first Heinrich in the family.

Some Notable Henrys

In the Civil War you will find one Henry Zumbrun in the 152nd Regiment for the Ohio Infantry in the Civil War, and another Henry Zumbrun, who served in the 7th Regiment of the Missouri Cavalry. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC, honors the memory of Sergeant First Class James Henry Zumbrun, a highly-decorated member of the Green Berets, who died in that war on January 10, 1970.

A quick search through readily available records finds Henry Zumbruns who were born in 1783, 1812, 1834, 1841, 1844, 1845, 1860, 1867, 1882, 1891, 1898, 1916, 1925 and 1926. (That includes Henry Zumbrun and Henry Sylvester Zumbrun, the ancestors of most of the Zumbruns living today in Indiana and Ohio.) It’s common as a middle name too. In addition to James Henry Zumbrun, I’ve found a Rock Henry Zumbrun, a Sylvester Henry Zumbrun, at least two different William Henry Zumbruns and two different John Henry Zumbruns over the years. (It’s also my middle name.)

The name Henry begins even before Johann Heinrich Zumbrunn, who married Maria Eva Lehr in Schwegenheim, Germany in 1749 and became the first Zumbrun in America. It begins before he arrived in Philadelphia and signed his name just, Heinrich Zumbrun. (Some records say that his son was also named Johann Heinrich Zumbrun, although most records call his son John Zumbrun or Johann Zumbrun.)

When I started researching the Zumbrunnen family of Switzerland, I quickly discovered the name was particularly common among the Zumbrunnen who lived in the Canton of Uri. Heinrich Zumbrunnen was the bailiff of Livinen from 1469 to 1472. Another Heinrich Zumbrunnen was the church bailiff of Altdorf in the 1500s. His son Johann Heinrich Zumbrunnen was the chief magistrate of Uri from 1621-1623, and again in 1637-1639. He had a grandson named Heinrich Burkhard Zumbrunnen. In the mid-1600s, a Josue Zumbrunnen had a son named Heinrich Zumbrunnen with his first wife, and another named Heinrich Zumbrunnen with his second wife. Yet another Johann Heinrich Zumbrunnen was born in Altdorf in 1668.

The Original Heinrich Zumbrunnen

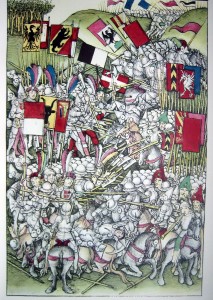

The Battle of Laupen, as drawn by Diebold Schilling, the author of the illustrated Chronicle of Bern in 1480.

The popularity of the name across seven centuries, seems to owe to the valor of the very first man who held the name. In the late 1200s or early 1300s, Burkhard Zumbrunnen, a Knight in the Order of St. Lazarus, had two sons named Johann Zumbrunnen and Heinrich Zumbrunnen. The younger son Heinrich is the one who would become a namesake across the centuries.

To set the stage, several generations of Zumbrunnen men had devoted their life’s work to building alliances to protect their territories against encroachment from feudal lords (such as Burkhard Zumbrunnen who helped create an alliance with Zurich in the year 1251). While most of Europe at the time was under the rule of various counts and dukes and princes and kings, central Switzerland had achieved a degree of independence. In the early 1300s, many aspiring tyrants, especially the Counts of Burgundy and the House of Hapsburg, dreamed of subjugating Switzerland. This is the era from which the famous story of William Tell emerges.

The city of Bern — today the capital of Switzerland — had been growing in wealth and power and population. This was nettlesome to the likes of the Hapsburgs because Bern was what’s know as a Free Imperial City of the Holy Roman Empire. The burgeoning city answered to the Holy Roman Emperor himself, but not to any intermediate kings or princes or dukes or counts. The Hapsburgs, the Counts of Burgundy and other power-hungry nobles raised a force of nearly 16,000 infantry and 1,000 heavily armored knights and seized the Bernese town of Laupen.

Bern called upon its allies in the mountainous regions of Switzerland. Johann Von Attinghausen, who had succeeded Burkhard as the chief magistrate of Uri, mustered a force of men, including Heinrich Zumbrunnen (who, as it happens, was Johann Von Attinghausen’s third or fourth cousin). In the early summer of 1339, they marched to Bern.

June 21, 1339

The troops of Bern and Uri and their allies in central Switzerland numbered only 6,000 but developed a plan to relieve Laupen despite being wildly outnumbered. On June 21, 1339, they assumed their position on a hill above the town.

A reenactment of the “Hedgehog” military formation

Meanwhile, the infantry forces of the Hapsburg alliance clashed with the forces from Bern. They say the victors write history, and according to the Bernese it was the valor of their men that carried the day. There may be some truth that the men fighting for the Hapsburgs lacked the conviction of the Swiss, who were fighting for their freedom and independence. It may also be that the inferior numbers of the Bernese had duped the Hapsburg alliance into a reckless uphill attack. Either way, the Bernese infantry quickly triumphed and then pivoted to attack the mounted knights.

Suddenly, the knights were no longer trying to penetrate the “hedgehog” of Uri; they were themselves surrounded. Some sources say as many as 80 of the Hapsburg-allied nobles died in the ensuing combat. The battle, at least for a few years, broke the back of the enemies of Swiss independence. The battle forever changed military tactics too, as it was one of the first conflicts demonstrating, against all odds, that a small (but brave and well-organized) infantry could defeat a force of heavily-armored knights. The success of such tactics is why medieval knights ultimately became obsolete.

The conflict was also famous as the first time the white cross, which would become the Swiss flag we know today, was used in battle. The men of Uri and Bern became heroic figures, fighting and dying beneath a common flag to protect each other’s independence. In 1353, Bern formally and permanently joined the Old Swiss Confederacy. Among those who perished in the ferocious combat was Heinrich, beneath the Swiss flag, quite likely holding a pike in that hedgehog formation against a large force of heavily-armored Hapsburg knights.

Monument of the Battle of Laupen, where Heinrich Zumbrunnen fell in battle in 1339.

Heinrich thus became a war hero back in Uri. His bravery at the Battle of Laupen would certainly have been known to the Zumbrunnen men of subsequent decades who named their sons Henry. Heinrich Zumbrunnen’s brother Johann lived until at least 1360. He was the author of early chronicles about Uri and may have helped build the legend of his fallen brother, though his chronicles have not survived. Johann Von Attinghausen, the leader of the Uri who survived the battle, likely brought back the story of Heinrich’s bravery as well.

Certainly the story of the battle was forgotten in the family at some point, though Heinrich’s name has remained in the Swiss history books. Who knows if the Heinrich Zumbrun, who arrived in America in 1754, had any knowledge of the battle, or if he only knew he’d been named after his father or grandfather.

But whether he knew it or not, he carried the name of a Swiss war hero to America, where it was anglicized to Henry and passed down again countless times so that nearly 700 years later, Heinrich Zumbrunnen’s death in the name of freedom and independence continues to echo through the family.

[…] HEINRICH died in 1339 in the Battle of Laupen. […]

[…] in 1339.(This made Heinrich into a hero, and seems to be the origin of the family tradition of naming people Heinrich/Henry.) Was the father […]

Im from wyoming and im a direct descendant of heinrich zumbrun,…he is my great great great great great grandfather,…awesome research btw